This article features otherwise unpublished food safety management data held by BRCGS and the monitoring module in Safefood 360° which, combined with real-time events, provides an unparalleled view of current and emerging issues and trends in the food safety industry.

Forever Chemicals

Our understanding of chemicals and the ability to manipulate them has led to the development of a multitude of substances with beneficial applications for humans. Like many developments, sometimes the very aspect that delivers benefit can also lead to unintended and less welcome properties and outcomes. Forever chemicals are one such group of compounds that have been used for over a century in products such as non-stick cookware, food packaging, water-repellent clothing, firefighting foams and pesticides. Their ability to confer water-, grease- and stain-resistant properties to products has led to their widespread use but their exceptional chemical stability, with many having been found to persist for years, has led to their widespread presence in the environment. This has resulted in concerns regarding the exposure to humans and the potential health risk that some may present to the public.

This article will explore forever chemicals, their history, uses, potential risks and measures being taken to mitigate this.

What are forever chemicals?

Forever chemicals consist of a number of chemicals that have particular physical and chemical properties that can remain intact for years and become widely distributed throughout the environment. The term forever chemicals is generically used to refer to a group of perfluorinated and polyfluorinated alkyl substances (PFAS) that comprise of thousands of man-made compounds that accumulate in the environment, food and humans over time. The definition of PFAS can vary but they generally consist of a carbon backbone with fluorines saturating most carbons and at least one functional group, such as a carboxylic acid, sulfonic acid, amine, or other.

PFAS may also be part of a broader group of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and dioxins that include chemicals persisting for long periods in the environment that can be toxic to both humans and wildlife.

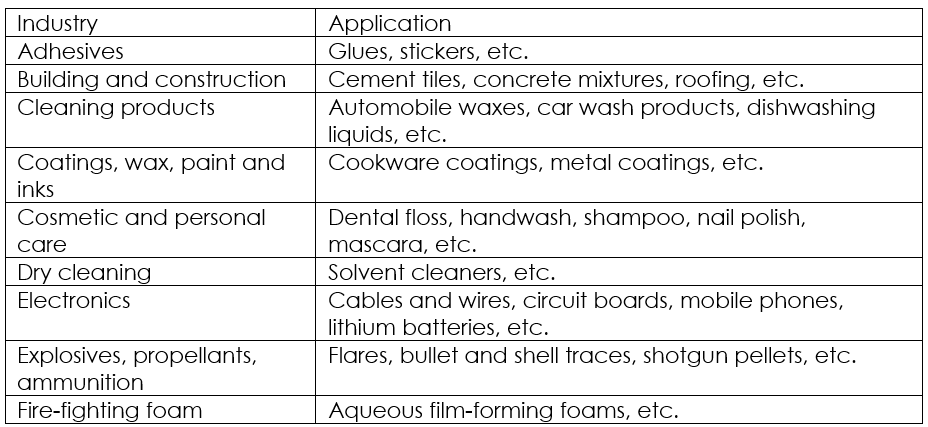

The uses of PFAS are exceptionally broad and an excellent review considered 25 broad industries and applications, some of which are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1: Industrial applications of PFAS

History of forever chemicals

The history of PFAS can be traced back to the mid 1800’s and to the work of Alexander Borodin. His work in organofluorine chemistry lead to the development of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) such as FreonÒ, used for industrial refrigeration from the early 1930’s. The first fluoroplastics were developed in the late1930s and included the well-known and universally used polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) or TeflonÔ. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS), two of the most extensively used (and consequently studied) PFAS began to appear in the 1950’s in stain and water-resistant coatings used for upholstery, carpeting, shoes, camping gear and clothing. Their use also extended into protective coatings for a wide array of food packaging over this period and now a wide range of other PFAS are used universally in food, non-food and consumer products globally.

Health risks

PFAS present a potential health risk to the public due to long term exposure and accumulation in the body. There are only a small number of PFAS that have been studied in the context of their toxicity to humans and, like many chemicals, their effects are most pronounced in those exposed to high levels as well as those who are in vulnerable groups such as children and the elderly. Of these few well studied PFAS, the European Environment Agency (EEA) considers most to be moderately to highly toxic to children’s development. The EEA provides a useful overview of the potential adverse health effects of exposure to PFAS, ranging from increased cancer risks (breast, kidney, testicular), thyroid disease, increased cholesterol levels to a variety of developmental defects affecting the unborn child during pregnancy. Although the potential toxicity of PFAS were not publicly established until the late 1990s, it is reported that risks were known for decades prior to this.

PFAS exposure is impossible to avoid and studies in recent years have reported high percentage prevalence in blood samples from populations. A recently published study of 1,500 blood samples in the Netherlands reported that the amount of PFAS exceeded health-based guidance values in “almost all cases”. Similarly, a study of PFAS levels in teenagers (12-18 years old) across a number of EU countries found that over a quarter had levels in their serum where adverse health effects cannot be excluded and 14.3% exceeded the EFSA guideline level of a tolerable weekly intake. In this study, the most relevant sources of exposure identified were drinking water and some foods (fish, eggs, offal and locally produced foods). A study in Australia reported the prevalence of 11 types of PFAS in blood samples with PFOS and PFOA being found in over 99% and 98% samples, respectively.

Regulation of PFAS

The increased recognition of potential adverse impacts of PFAS to humans, animals and the environment has stimulated significant scientific risk assessment and associated regulatory control. However, this has resulted in somewhat differing approaches across the world and also in different industries.

The Stockholm Convention was one of the first attempts to manage the risk associated with these types of chemicals. Adopted in 2001 and coming into force in 2004 the convention had the objective to protect human health and the environment from the wider group of persistent organic pollutants. Specifically, it listed chemicals that should be prohibited and/or eliminated in their intentional production and use (including import and export), chemicals that should be restricted in their intentional production and use and chemicals where their release through unintentional production should be reduced or eliminated. The current list of 33 prohibited/eliminated chemicals (Annex A of the Convention) include many pesticides, polychlorinated compounds such as PCBs and PFAS (PFHxS and PFOA), although a variety of specific exemptions are included.

Actions introduced by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) include a variety of measures to monitor, manage and dispose of PFAS together with a specific regulation for drinking water with legally enforceable maximum contaminant levels (MCLs), for six PFAS in drinking water specifying levels as low as four parts per trillion (nanograms per litre) for PFOA and PFOS.

In the European Union, the European Chemicals Agency regulates controls in relation to risks from chemical hazards and provides an overview of their regulatory approach to the management of PFAS. Specifically, the REACH Regulations (Registration, Evaluation, Authorization and Restriction of Chemicals) lists a number of PFAS as substances of very high concern and also has several others as candidate SVHCs. Similarly, PFAS are restricted in the regulations for Persistent Organic Pollutants, Waste and Drinking Water. The use of some PFAS have been prohibited in fire-fighting foams and further restrictions are planned. A recent proposal by some EU member states aims to further restrict the use of a wider range of PFAS. In relation to food and water, the Water Directive introduced a limit of 0.5 µg/l for all PFAS and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) set a new safety threshold (a group tolerable weekly intake, TWI) in food of 4.4 nanograms per kilogram of body weight per week for the main perfluoroalkyl substances that accumulate in the body: PFOA, PFOS, PFNA and PFHxS. This followed a European Commission recommendation for EU member states to monitor for PFAS in foods.

Analysis of PFAS

Testing for PFAS in products is key to understanding the exposure to the public and determining the associated health risks. Testing of this nature is highly specialised and should be conducted in suitably accredited laboratories, with demonstrable capability to detect the contaminants at the sensitivity and in the relevant matrices required. Consideration of sampling, test methods and choice of laboratories for analytical testing have been extensively covered in a previous Article (DN: Insert Link to Analytical Assurance article).

Testing for PFAs has revealed how widespread and varied levels of PFAS can be. A recent interactive map of PFAS in food, water and the environment has been compiled by a group of journalists using publicly available data sources across the UK and Europe.

The management of analytical data together with risk assessment of raw materials, products and associated suppliers can be supported through the use of integrated software solutions such as Safefood 360°.

Summary

Despite recent efforts to regulate the use of PFAS and a reduction of the use of certain specific PFAS, it is almost impossible to avoid exposure to these chemicals. I hope this article has given you a reminder of the current status of thinking regarding the use, risks and regulatory controls of PFAS but it is clear that this topic will continue to receive significant attention of risk assessors and this will lead to further actions required of industry to mitigate this risk to the public.

|

AuthorAlec Kyriakides Independent Food Safety Consultant |